A recent scam made use of two different fake Facebook profiles to try and trick me into divulging my identity data and a picture of my driver’s license. I describe the incident here to both remind consumers to be wary on Facebook and to spread awareness of how scammers employ fake profiles in order to defraud people on Facebook.

This article should also caution organizations that, despite social media platforms’ best (or lackluster) efforts, you can’t count on them to adequately defend your brand or reputation online. The example below may serve as proof of that — a profile impersonating a US government employee and attempting to steal identity information was not enough to spur enforcement action from Facebook.

Modern online brand protection requires automated monitoring for online brand impersonation across web sites, social media platforms, and mobile app marketplaces and multi-pronged response along with diligent follow-up with registrars, hosts, social media platforms and more in order to protect prospects and customers against fraudsters.

Executive Summary

Here’s a quick overview of the incident:

- Months ago I received a Facebook connection request from a friend I thought I was already connected with, but I accepted it anyway

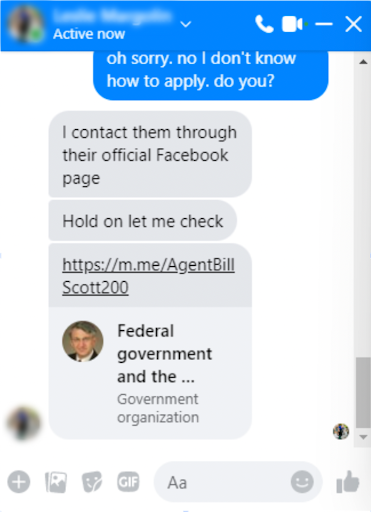

- The request came from what ended up being a profile impersonating my friend and the impersonator eventually reached out to me over Facebook Messenger

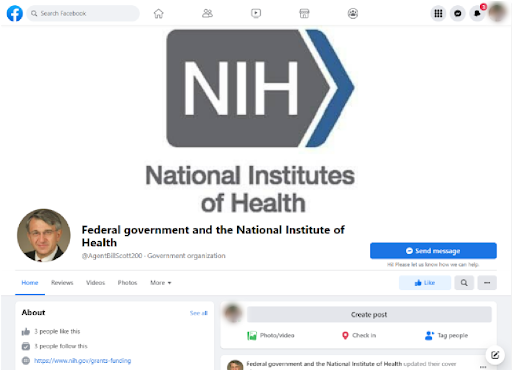

- The impersonator directed me to a fake profile that used someone else’s photograph as a profile picture and impersonated an employee of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the guise of applying for a grant

- That fake NIH employee’s account attempted to steal identity information from me including a picture of my driver’s license

- That fake NIH employee’s account remains live nearly a month later despite my reporting it multiple times

Step 1 of the con: Impersonate a trusted friend’s Facebook profile

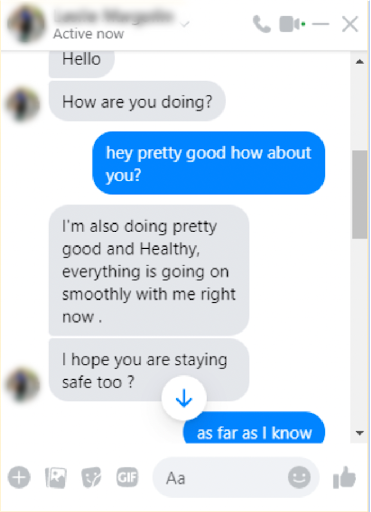

On a Wednesday morning, a friend that I’d never before spoken to over Facebook messenger asked me how I was doing and whether I was “staying safe.” This friend of mine does not own a mobile phone, but he typically communicates with me over e-mail. He also let me know everything was going “smoothly.” The word choice struck me as uncharacteristic.

The friend then inquired about whether I had heard about the “Federal Government and National Institute of Health Grant program.” I immediately sent a picture of the exchange over SMS to the friend’s wife (because, again, this individual doesn’t have a mobile phone). I asked her to tell him his account had been hacked and to change his password. I also told the scammer that I thought they should spend their time on more honest endeavors.

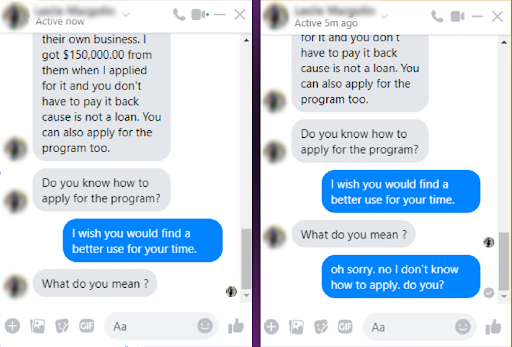

I also checked what I thought was my friend’s profile to see if the attacker had also posted links to the grant scam or discounted handbags, sunglasses, and other goods on their feed. However, there was no content in the feed. Though the profile did have three mutual friend connections.

I had seen this person comment on Facebook before and recognized the profile picture (the friend, his wife, and a dog). But why did he only have three friends and no posts? Had he “rage-quit” Facebook but then regretted it and re-registered?

I remembered having accepted a friend request from him some months ago. I wondered about it at the time because I could have sworn I was already friends with him. But again, I thought maybe he had quit Facebook for a bit then decided to start using it again.

Incidentally, a week or so before this, I received a friend request from a former colleague that I knew I was already connected to on Facebook. In that instance, the profile had no picture which made me suspicious. Sure enough, I searched and found the real colleague’s profile and reported the fake.

Remembering this I decided to search for this friend’s name and sure enough found two profiles using the same profile picture and name. I then realized what had happened. A scammer impersonated this friend in order to invite me to a scam.

Tip: When you get a friend request, spend a little more time looking at the profile rather than simply accepting the request. You may have no reason to suspect the request itself with limited information available to you. But if you click through to the profile you may find it was created mere days ago, has not posted any content (or posted obviously “scammy” content), or has few if any friends. In addition, consider yourself a first line of defense for your other connections. Connecting with the fake profile lends it legitimacy in the eyes of your other connections and potential victims.

Now, those of you saying – “well you should have been suspicious of a profile with no posts and only three friends.” I agree, but consider that when someone communicates with you through Facebook messenger, there’s not much context there. If the profile name and photo match what you might be used to seeing in your feed, you may not give it a second thought.

Tip: When a Facebook connection reaches out to you over Facebook Messenger, take a second and look at the individual’s profile before you engage in conversation (click the inverted caret next to the name and then “View profile.” Also, every once in a while it makes sense to search your own name on Facebook and other social media platforms to see if anyone is impersonating you.

At this point, I knew I was dealing with an impersonator, but I decided to play along to see where the scam was heading.

Step 2 of the swindle: Pose as an employee of a trusted institution or brand on Facebook

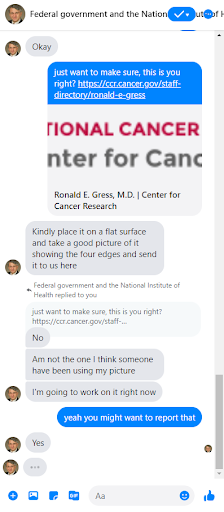

Next, the imposter directed me to another account, “Federal Government and the National Institute of Health,” administered by Agent Bill Scott. And following the original imposter’s instructions I clicked on the “Send message” button.

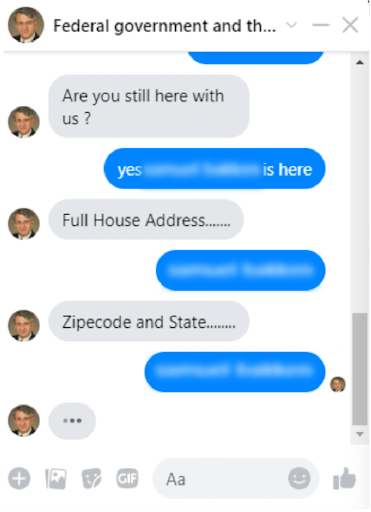

From there, “Agent Bill Scott” asked me for my name, mailing address, gender, birthdate, phone number, e-mail address, and more.

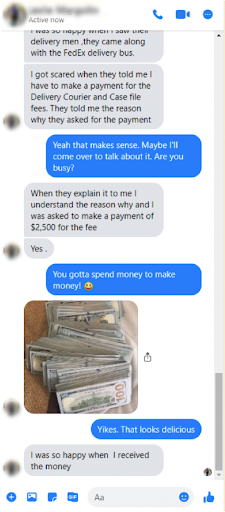

Finally, Agent Bill asked me for a picture of myself. I re-engaged with the first imposter telling them I thought the request for the photo was odd and made me wonder whether it was a scam. The impersonated friend lives just blocks away so I also asked the impersonator if they were busy or if I could stop by to discuss the opportunity in person. They were busy but reassured me that they also worried it was a scam at first but then FedEx arrived with their cash. They also told me not to worry about the $2,500 delivery courier and case file fees.

I did a quick Google Image search of the photo used on the profile. It turned out to be a photo of Ronald E. Gress, M.D. of the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. As I continued stalling on providing a photo of myself, I sent Agent Bill’s profile picture to him and asked whether he was Ronald E Gress. The fraudster explained that someone else was using his picture. In addition, the imposter had grown tired of waiting for me to send a picture of myself and asked that I send a picture of my driver’s license.

And that’s where I stopped interacting with the fraudster.

Lesson for brands and government institutions: You can’t count on Facebook to care as much about your brand as you do

After the incident, I reported the profile impersonating my friend on Facebook and alerted the three others that had connected with the impersonator. That same day, the account was no longer accessible. I don’t know if Facebook took action on the report or if the impersonator took the profile down themselves.

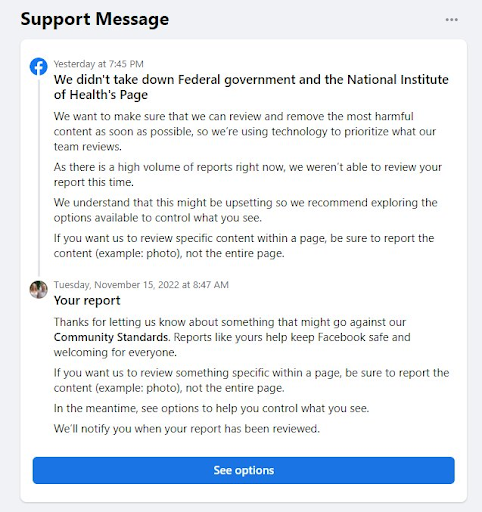

On November 15, I then reported Agent Bill Scott’s government organization profile for the Federal government and the National Institute of Health as a scam and fake page. Three days later, Facebook notified me that they would not take down the page because their automated system did not diagnose the fake as worthy of review.

I assume that the Facebook content moderation team receives an incredible volume of reports of offending content. I accept that using artificial intelligence to triage the reports is reasonable. Meta’s policies on taking down content mentions that a page must repeatedly violate Facebook community standards. Perhaps I was the first person to report the page.

Meta states that it prioritizes content for review based on:

- SEVERITY – How likely is it that the content could lead to harm, both online and offline?

- VIRALITY – How quickly is the content being shared?

- LIKELIHOOD OF VIOLATING – How likely is it that the content in question does in fact violate our policies

In terms of severity, the account engaged in identity theft up to and including requesting a picture of my government ID. Granted, the scammers weren’t particularly clever (other than the impersonation of a friend of mine to invite me to the scam). Had I given them real information about myself and a picture of my driver’s license, I suspect financial harm wouldn’t be far behind.

With regard to virility – granted, I wouldn’t believe that a whole lot of people share the fake Federal Government and National Institutes of Health page in their feeds. However, I do suspect that the scammers have a stable of fake profiles impersonating people’s friends. They then use those fake profiles to reach out to people over Facebook Messenger. So, this particular page may not meet Meta’s virility threshold.

Considering “likelihood of violating,” the page explicitly violates Facebook’s community standards related to authenticity: “We want to make sure the content people see on Facebook is authentic. We believe that authenticity creates a better environment for sharing, and that’s why we don’t want people using Facebook to misrepresent who they are or what they’re doing.”

The importance of reputation in responding to online brand impersonations

If I’m completely honest, I don’t blame Facebook necessarily for rejecting my report. I’m just one person that has reported very few, if any, violations in the past. I do think the report should have still gone to a human review board. I can’t see any reason the page could be thought to have any good intentions.

Regardless, it does demonstrate the importance of working with experts that understand the social media platform’s processes and procedures for handling deceptive content. Ideally, those experts should also have a track record of success with takedowns.

In October, Meta did announce new features to make it easier for brands to report content impersonating them or violating their intellectual property on Facebook or Instagram. This looks like a real step forward for Facebook and Instagram. Allure Security (and other providers like us) have been asking Facebook for a more formalized documented process for submitting infringing content for a long time. Building in a reputation item – a “demonstrated history of actionable requests” – is a smart move too whereby submitters with a record of submitting accurate reports will see action faster than they have in the past.

However, it’s important to realize that brands can’t count on the social media platforms to care as much about their brand and its use as much as the company itself and their customers do. So while these actions will accelerate response on Facebook/Instagram’s side, the platforms won’t find every single ad, shopping listing, and Facebook or Instagram page that violates trademarks, infringes on copyrights, peddles fake or counterfeit products, or impersonates a brand. It also remains to be seen how brands that have not yet established a “strong reporting history” have fared in terms of resolving this deceptive content.

Brands also need to evaluate whether building this sort of expertise in-house is worth it. In the current economic climate, cybersecurity, risk, marketing, and legal teams are being asked to do more with less. Estimates peg the cost of hunting and responding to online brand impersonations at $150,000 or 3,000 hours of an analyst’s time. Add to that the estimated cost of mitigating a single incident which is $14,700 including analyst and lawyer time. Brands have better things to do than have employees manually searching social media platforms for violations.

Brand protection vendors such as Allure Security have built technology specifically to seek out online brand impersonations across the web, social media, and mobile app marketplaces. In addition, many vendors have already built a reputation with the platforms so that takedowns occur more quickly.

What You Should Do Next

- Learn more about online brand protection and your options for protecting your organization’s brand online with our free Busy Person’s Guide to Online Brand Protection

- Get the skinny on Gartner® recognizing Allure Security in its 2022 Emerging Tech: Adoption Growth Insights in Digital Risk Protection Services Report and what sets our online brand protection-as-a-service apart on our blog

- If you’re ready to talk about your online brand impersonation detection and response program and how Allure Security can improve your effectiveness and reduce costs, contact us.